What is scoliosis?

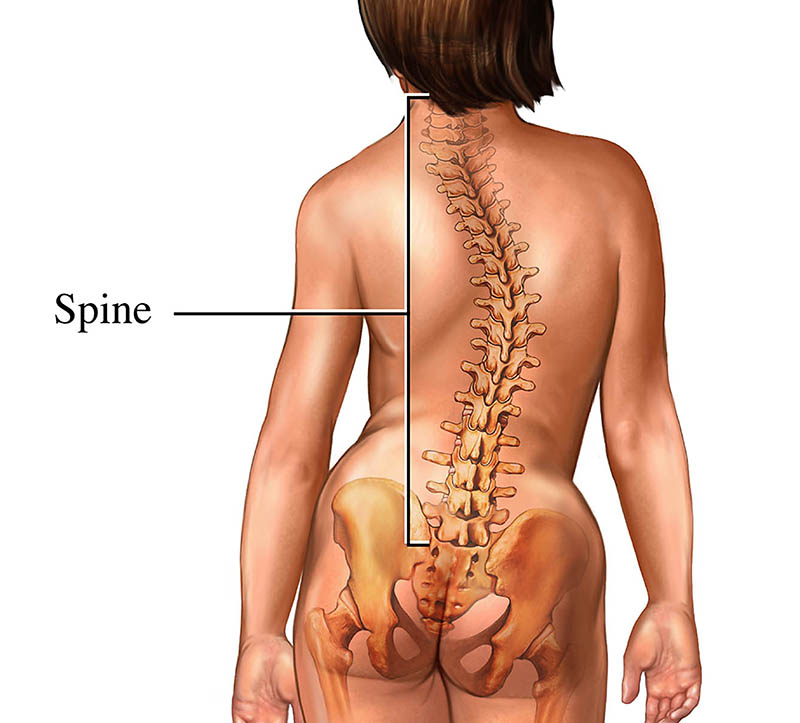

The spine is made up of a stack of rectangular-shaped building blocks called vertebrae. When viewed from behind, the spine normally appears straight. However, a spine affected by scoliosis is curved — often appearing like an S or C — with a rotation of the vertebrae. This curvature gives the appearance that the person is leaning to one side.

Scoliosis is determined when the curvature of the spine measures 10 degrees or greater on an X-ray. Spinal curvature from scoliosis may occur on the right or left side of the spine, or on both sides in different sections. Both the thoracic (mid) and lumbar (lower) spine may be affected by scoliosis. Scoliosis is a type of spinal deformity.

In more than 80 percent of cases, the cause of scoliosis is unknown — a condition called idiopathic scoliosis. In other cases, scoliosis may develop as a result of degeneration of the spinal discs, as seen with arthritis, osteoporosis or as a hereditary condition that tends to run in families.

What are the different types of scoliosis?

Congenital Scoliosis

In congenital scoliosis, spinal curvature develops because of misshapen vertebrae. The diagnosis of congenital scoliosis may be made in early infancy if outward signs are present, but many cases are diagnosed later in childhood.

As a child grows, scoliosis may worsen, and asymmetries in the body may develop. Typically, congenital scoliosis is treated with a “watch and wait” approach. Surgery is considered only if a curve is clearly getting worse and the child is facing ongoing deformity and risk of future pain.

Idiopathic Scoliosis

Doctors, nurses and scientists have been studying the natural history and genetics of scoliosis for decades, but to this day, the cause of idiopathic scoliosis is still unknown. But we do know that the most common time for idiopathic scoliosis to develop is at the onset of adolescence, or around the age of 10. We also know that growth can make it worse, and we should be most concerned about scoliosis in a child that has significant growth remaining.

When diagnosed in children 2 or younger, this type of scoliosis is called infantile idiopathic scoliosis.

Neuromuscular Scoliosis

A child with an underlying neuromuscular condition is at higher risk for developing scoliosis. A straight spine requires normal muscle balance and strength in the torso. In conditions such as cerebral palsy, spina bifida and muscular dystrophy, the muscles are often weak and unbalanced, leading to the development of a spinal curvature.

A child with neuromuscular scoliosis is given the option of wearing a scoliosis brace that may slow or prevent the worsening of the condition. Surgical intervention is offered when the curve has reached the tipping point of 50 degrees. Over time, these curves will continue to worsen, leading to progressive imbalance of the torso. Beyond 80 degrees, breathing challenges develop as space for the lungs decreases.

What are the symptoms of scoliosis?

The following are the most common symptoms of scoliosis. However, each individual may experience symptoms differently. Symptoms may include:

- Difference in shoulder height

- The head isn’t centered with the rest of the body

- Difference in hip height or position

- Difference in shoulder blade height or position

- When standing straight, difference in the way the arms hang beside the body

- When bending forward, the sides of the back appear different in height

- Prominence or asymmetry in the ribs seen from the front or back

The symptoms of scoliosis may resemble other spinal conditions or deformities or may be a result of an injury or infection. Always consult your doctor for a diagnosis.

Symptoms that are not commonly associated with idiopathic scoliosis are back pain, leg pain, and changes in bowel and bladder habits. If a person is experiencing these types of symptoms, he or she requires immediate further medical evaluation by a doctor to determine the cause of the symptoms.

How is scoliosis diagnosed?

Early detection of scoliosis is most important for successful treatment. In addition to a complete medical history and physical examination, an X-ray is the primary diagnostic tool for scoliosis. In establishing a diagnosis of scoliosis, the doctor measures the degree of spinal curvature on the X-ray.

The following additional diagnostic procedures may be performed for nonidiopathic curvatures, atypical curve patterns or congenital scoliosis:

- MRI. This diagnostic procedure uses a combination of large magnets and a computer to produce detailed images of organs and structures within the body.

- CT scan. This diagnostic imaging procedure uses a combination of X-rays and computer technology to produce horizontal, or axial, images (often called slices) of the body. A CT scan shows detailed images of any part of the body, including the bones, muscles, fat and organs. CT scans are more detailed than general X-rays.

How is scoliosis treated?

The goal of treatment is to stop the progression of the curve and prevent deformity. Observation and repeated examinations — also referred to as the “watch and wait” approach — may be necessary to determine if the spine is continuing to curve. These are used when a person has a curve that is less than 20 degrees and who is still growing.

For actively growing children with scoliosis curves between 20 and 50 degrees, bracing is recommended. An external torso brace, or TLSO, is worn for a prescribed number of hours. The brace applies corrective pressure to the growing spine, preventing further worsening of the scoliosis.

Surgery is a recommended treatment option for a child with severe scoliosis or a curve that has worsened to more than 50 degrees. At the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center, our team of pediatric spine surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists use a family-centered approach to develop a plan for the care of your child. We are a high-volume scoliosis center, and we are constantly learning and adopting best practices for the operative and postoperative care of children with scoliosis.